A gecko with “giant eyes” and another master of camouflage among the newly discovered

Scientists describe three new species of day geckos in southern Angola, with giant eyes, expert camouflage, and unique habitats.

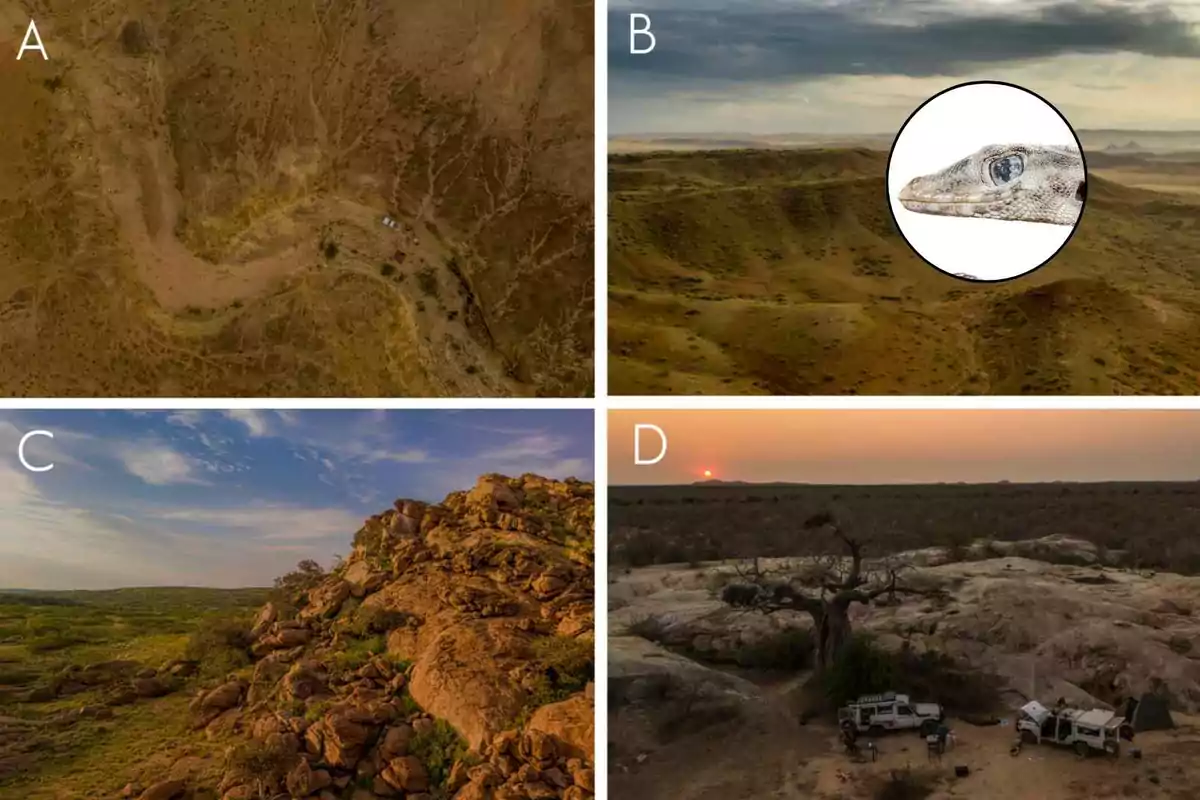

The Namib’s sun baked rocks just got busier. A team working in southern Angola has described three new species of Namib day geckos, each with its own appearance and preferred habitats, tucked into the coastal landscapes of Namibe Province.

Meet the newcomers: Rhoptropus minimus (a pocket sized, ground runner), Rhoptropus megocellus (a big gecko with jumbo “eyespots”), and Rhoptropus crypticus (a camo specialist on boulders). Together they push Angola’s described gecko tally higher and spotlight the Bentiaba area as a mini hotbed of reptile endemism. In the paper’s time‑tree, several Rhoptropus lineages split during the Miocene, with some divergences tracing back to more than 17 million years.

Who conducted the study?

The work was led by Javier Lobón Rovira at CIBIO–InBIO, University of Porto, alongside collaborators from the University of Michigan–Dearborn, Villanova University, and Nelson Mandela University, with Angolan partners including Fundação Kissama. The paper credits field surveys across southwestern Angola between 2018 and early 2025.

Specimens are housed in collections in Luanda, Porto, and Madrid, and genetic data was deposited in GenBank. The authors followed veterinary guidance for humane euthanasia in line with AVMA guidelines.

What the researchers did

The team combined old‑fashioned herping searching for rocks, gullies, and sand flats with lab work on mitochondrial and nuclear DNA. They analyzed 16S, ND2, and RAG‑1 sequences, and built both maximum likelihood and Bayesian trees to test where oddball populations fit.

They also measured body proportions and scale traits, then matched those details to color patterns and habitat use. A dated “time tree” was generated using BEAST to estimate when each branch diverged.

What they discovered

Three populations stood out as full species. R. minimus is tiny (under about 39 millimeters from snout to vent), pale granite in pattern, and races across open gravel and sand; males have four precloacal pores in two small groups. R. megocellus is large, with pairs of bold black ocelli along the back and paired enlarged subcaudal scales, a hallmark of its lineage.

R. crypticus looks like a mashup: a highland style orange head reticulation fading to coastal grays, plus a single row of enlarged subcaudals, and black spotting that separates it from close relatives. All three are restricted to northern Namibe Province, especially around Bentiaba and nearby granite fields.

Where the geckos live

R. minimus favors flat, open sedimentary ground, thick gravel fans and sand sheets dotted with fist sized stones north of Moçâmedes and around Baba and Praia do Soba. At the southern edge of its range near Iona National Park, it gives way to the larger, ground running R. biporosus, and the two have not been found side by side.

R. megocellus and R. crypticus are rock specialists on big, exfoliating granite slabs and vertical faces near Bentiaba and Chapeu Armado. They can occur alongside R. boultoni, using slightly different parts of the same boulder stacks.

How old are these lineages?

Across the species, the study’s dated tree shows a major split separating coastal and highland clades, with many branches forming between the mid and late Miocene. For example, the R. taeniostictus group (which includes R. megocellus) diverged from its nearest relatives more than 17 million years ago, with its two species parting ways sometime between about 4 and 10 million years ago.

The authors note a second burst of speciation within the R. barnardi group home to R. minimus during the late Miocene to Pliocene. That timing echoes broader African diversification pulses discussed in Heinicke et al. 2017 and Plana 2004.

Why is it important?

Taxonomy isn’t just name tags; it maps biodiversity, so land administrators know what they’re protecting. By revealing three local endemics with very narrow ranges, the study flags the Bentiaba coastline as a conservation priority during road building, mining, and tourism growth.

It also helps fix long-standing mix-ups in a species where look‑alikes live shoulder to shoulder. Clear DNA and diagnosable traits reduce misidentifications that have slowed progress on Rhoptropus since the 1990s and sharpen future ecological work.

How the findings fit the bigger gecko picture

Rhoptropus, a group of fast, diurnal, rock accustomed geckos, is concentrated in Namibia and Angola. Angola now emerges as a major hub for the group’s diversity. The Reptile Database lists Angola among Africa’s gecko hot spots, and the new species reinforces that status.

Similar coastal patterns vs. escarpment splits, with episodes of mixing show up in other southern African reptiles. Studies on Afroedura from Angola and Namibia, for instance, found closely related rock geckos carving up habitat across inselbergs and cliffs (Conradie et al. 2022).

Warnings to keep in mind

Two of the newcomers appear confined to a handful of hills. Narrow ranges make species vulnerable to localized threats, from quarrying to off‑road traffic, even if they seem “common” on a single slope. The authors stress that similar habitats are scarce around Bentiaba, which likely increases isolation for R. crypticus.

And while the genetics are clear for the three species described here, the team urges caution on a separate candidate lineage within the R. barnardi group. Some mitochondrial and nuclear signals don’t line up neatly, so next generation sequencing will be needed before any more nameplates go up.

Study: Lobón‑Rovira, Heinicke, Bauer, Conradie & Vaz Pinto, 2025, in Ecology and Evolution.

More posts: